by Joe McCormack

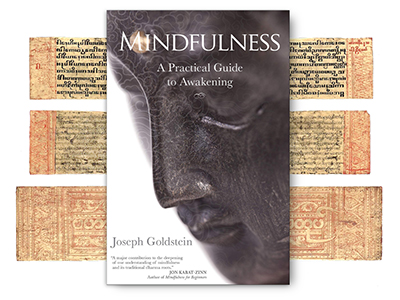

Mid-America Dharma is offering a six month book study class on the book Mindfulness: A Practical Guide to Awakening by Joseph Goldstein. This is a follow up to a six session pilot class held during the fall of 2021 and early winter of this year. To my mind, Joseph’s book is the most comprehensive and clear description of the practices of Four Foundations of Mindfulness. It should be a great class.

I wanted to share a few thoughts pertinent to Joseph’s book. In particular, we speak of this practice as one of Insight Meditation. But what do we mean when we say we have had an insight? What constitutes an insight?

Insights happen in our everyday lives and can involve anything from discovering an understanding about some event in our lives, to what someone really .meant when they said something, to understanding what a person’s (or our own) motivation was for something they did. The understandings coming from those insights can help us see our everyday lives more clearly and help us make wiser choices.

The insights that happen in Insight Meditation are in some ways similar, and in other ways different. They are similar in that they are discoveries. They differ in that often the territory of insights in meditation are on a different plane. There are actually several ways to discuss this. So I want to talk about three or four characteristics of insight in Insight Meditation practice.

First of all, an insight is spontaneous. Insights happen in such a way that you can’t plan for them to happen. We can do the work, letting go of attachment to outcome. Practice does result in insights, but we can never plan for them. A way of saying this is that insights happen by accident, and that the practice makes us more accident prone. And insights are surprising—they don’t involve well-rehearsed concepts.

Insights are typically non-conceptual. They don’t involve the discursive, conceptual mind. So while insights often happen in the realm of Buddhist principles, the nature of an insight is anything but philosophical. It is a lived experience, and results in a changed felt sense of how life is or how our minds are. Thus, they arise in the present moment and there is usually a direct, immediate experience of the insight.

In contrast to mundane insights that often get the mind moving into (often productive) strategizing about how to solve one problem or another in our lives, one of the qualities of an insight in meditation is that it quiets the mind in a profound sense.

The usual machinations of the mind grind to a halt. This does not mean that the mind is quieted forever; discursive thought comes back quickly enough. But in the immediate wake of an insight arising, the mind is silent and peaceful (and often not thinking of anything particular). And that quieting of the mind can be freeing—sometimes in small ways, and sometimes in profound, life changing ways.

After experiencing an insight, it is beneficial and even necessary to bring concepts in after the experience of the insight to integrate more fully what the insight means.

So, this means that while insights spontaneously arise and are immediate and not conceptual, that does not mean that concepts are meaningless in the practice. Concepts can put a direct, immediate insight into a context. In some instances, people with no religious background can have a sudden spiritual awakening. That opening can be blissful for a second, but then it is disruptive. This is because that opening shakes the structure of our customary ways of experiencing life and the self, but with no spiritual tradition or set of concepts that can provide an under-girding for understanding what just happened.

It is here that having been exposed to the teachings (of any tradition) can be really helpful. If you have an opening it is liberating, but if you have no framework for understanding what just happened, then it is possible that the experience won’t be recognized as significant in the first place. So having the teachings in the back (not the front) of the mind is quite helpful. And the understanding can be helpful in framing the next steps in the process.

One of the advantages of the early discourses of the Buddha is that it has a structure that does really fit together and elucidate steps in the process.

Also, after an insight takes place, there is something called reviewing consciousness that comes in and looks back on the immediate, non-conceptual insight, and reviews it, and the teachings are helpful here.

One of the lenses by which we can develop insight into life as it is are what are called in Buddhism the Three Characteristics of Existence. I would like to briefly describe each of them, and subsequently we can see how we can experience insights, using as our guide the Buddha’s teachings on the Four Foundations of Mindfulness.

The Three Characteristics of Existence are: a) impermanence or anicca, the recognition that all of life is changing, including ourselves at every moment; b) unsatisfactoriness or dukkha, the recognition that no experience, however pleasurable, provides lasting satisfaction; and c) not-self or anatta, the recognition that there is no solid entity in anything we see, including ourselves, which are also subject to change and very limited control. When we see these clearly, we live our lives aligned with Truth and go more smoothly; when we don’t see these clearly, it results in ignorance and sometimes unwise choices that lead to suffering.

The First Foundation of Mindfulness is that of the Body. Some of the insights that can arise from mindfulness of the body are: a) noticing that the body changes, an insight into impermanence—this may seem trivial, but for most of us when we start practice, we take this for granted, and don’t really get it. This can be on the cushion, when a pain in the knee spontaneously goes away and we notice it, another insight into impermanence. Off the cushion, as we begin to see the changes in the body as we age, we can notice how those changes are happening due to causes and conditions, and out of our direct control.

The Second Foundation of Mindfulness, Feeling States, can yield insights in several ways. First and foremost, we find that feeling tone—pleasant, painful, or neutral—comes and goes, and that in any moment we don’t have control over what feeling state arises in that or the next moment. Another insight can be that of seeing the connection between pleasant feeling tone and grasping; painful ones and aversion, and neutral ones and inattention.

With Mindfulness of States of Consciousness, we can see how states of mind come up without choice—most of the time we have no control over what comes up next. Most of us do not wake up intending to be in a bad mood—it just happens. We also begin to see that states of mind arise and cease on their own, and as we see that there is a habitual quality to them that we don’t choose, we gain an insight into not-self. We can also begin the process of letting go of our identification with each mind state that arises, as we see that there is no abiding me there.

Finally, with Mindfulness of Dhammas or Mental Objects, we begin to see the process of causes and conditions that give rise to joyful states of mind and also mind states that result in misery, and in that process of seeing causality, we also let go of the idea of a self that is directing the process.

Insight practice leads to freedom. When we see clearly, the tendency to cling to satisfactions and identities that are impermanent and that we cannot control dissolves, at first in small ways, and as the practice continues, in more depth. I invite you to the book study class beginning April 23rd, and we will explore the process of insight more deeply.

Joe McCormack has practiced Insight Meditation since 1995 and has been a member of the Show Me Dharma Teachers Council since 2002. Joe leads an insight meditation group in Jefferson City, and has taught insight meditation to prison inmates since 1998. His teachers include Ginny Morgan, Phil Jones, and Matthew Flickstein. In January 2008, he completed the Community Dharma Leader training program through Spirit Rock Meditation Center. In his dharma instruction, Joe draws from traditional Theravada Buddhist teachings, Zen and Dzogchen practice, Advaita teachings, and the Diamond Approach. He is also trained as a psychologist and practices psychotherapy in Jefferson City.

Back to Spring 2022 Newsletter

.